M&A Blog #10 – equity (accretion / dilution)

Before we move on to the buy-side and sell-side process of M&A next week, I’d like to wrap up this week by discussing the other capital structure component / tool: equity. If you are a homeowner, you know that equity is the part of the home value that you actually own (as opposed to be owned by the bank). The concept can be extended to corporation: equity owners (shareholders) own the company alongside debt holders (banks). As we mentioned in the past, equity is the most expensive form of capital (compared to debt with tax-deductible interest). However it is also the most flexible. Equity providers’ claim on capital is contingent on company’s performance, so they earn a windfall if the company perform well and bear the brunt of any financial downturn. They are last in line to be paid in liquidation with their variable claim on capital. We care about equity in M&A because a successful transaction is one that creates value for equity holders. If an equity holder (shareholder) deem that a specific transaction has failed to create value badly enough, the company might be open to a shareholder lawsuit - perhaps even a class action shareholder lawsuit from multiple shareholders. In this post, we will discuss how to quickly gauge if a potential acquisition will create value or not for a public company.

I chose a public company for this exercise because private company financial statements don’t immediately lend themselves to the accretion / dilution analysis that we are about to review. Public company audited financial statements typically receive a good deal of scrutiny from accountants, equity analysts, and regulatory agencies. They are meant to provide accurate picture of the company’s financial health to investors, lenders, suppliers, and customers - so, typically has a bias of showing higher earning per share (EPS) as company management is aligned with EPS increases. Private companies have a different set of goals - that is to minimize taxes, so the private company accounting tend to minimize earnings. To do so, a private company would:

Expense an item that a public company would capitalize

Aggressively write down inventory

Distribute perks and benefits to management (cars, yachts, etc.)

Shift management and shareholders’ private expenses into company costs

A public and private company financial statements can’t be directly compared apples-to-apples. Significant adjustments on the private company’s financial statement would be needed.

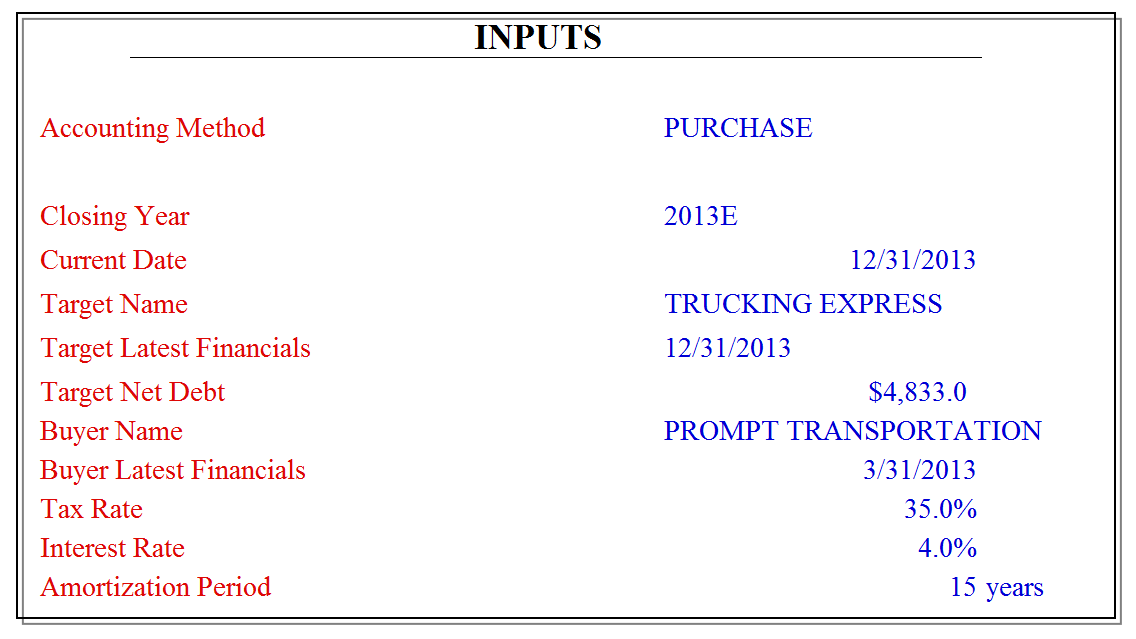

As a quick gauge of the attractiveness of a potential target, we should look at the company’s EPS before and after the proposed transaction. This analysis is known as the accretion / dilution analysis. Basically, if pro-forma EPS accretes (increases in value), the target is attractive. Otherwise, if pro-forma EPS gets diluted (decreases in value), the target is not attractive. To showcase how this analysis is done, we look at the attached sample file and the following assumptions:

The Target:

Name: TRUCKING EXPRESS

Inputs: last 12 months (LTM) Sales, EBITDA, EBIT (Net Income), Net Debt, and Book Value of Equity

The Acquirer:

Name: PROMPT TRANSPORTATION (public company)

Inputs: current stock price, LTM Sales, Net Income (Earnings), Shares Outstanding, Current (before transaction) EPS

Transaction Assumptions:

Horizontal acquisition to increase net income

The tax rate is 35%

The EBITDA multiple paid for the target is 4.6x

The acquisition will be 100% cash, paid for with debt at 4% interest rate. The interest expense is tax-deductible (tax shield).

The goodwill created from this transaction will be amortized over 15 years period

The synergies assumed amount to $1MM

The steps for the accretion / dilution analysis is fairly simple:

Sales: the pro-forma number will simply be the addition of the two companies’ sales

Net Income Before Transaction Adjustments: the pro-forma number will simply be the addition of the two companies’ net income

Adjustments:

Synergies Assumed (Net of Taxes) is simply the expected synergies - tax at 35%

Interest Expense is simply the purchase price financed by cash (which is 100%) * the interest rate of 4%

Amortization of Goodwill is simply (Purchase Price - Target’s Net Debt - Target’s Book Value of Equity) / Amortization Period of 15 years

Reduction in Taxes due Interest Expense is simply the Interest Expense * Tax Rate

The sum of the 4 bullets above amounts to Net Adjustments

Adjusted Net Income: is simply Net Income Before Transaction Adjustments - Net Adjustments

Adjusted (pro-forma) EPS: is simply Adjusted Net Income / Acquirer’s Shares Outstanding

The Percentage Accretion / Dilution: is simply the Acquirer’s (Adjusted EPS - Current EPS) / Current EPS. If this percentage is positive, that means the transaction is attractive because the EPS is expected to accrete.

As you can deduce, we can relax any of these assumptions. For example, if the acquirer’s want to purchase the target using the acquirer’s stock (zero cash transaction), we can still use this model by zeroing out the % Cash assumption. The model will automatically recalculate using an all-stock acquisition structure. The resulting Percentage Accretion / Dilution will be lower because of the new shares that have to be issued to finance the transaction.

The accretion / dilution analysis is a common exercise for most public acquirers. Management teams are usually concerned that any acquisition will dilute EPS, especially so if management incentives (bonus) is tied to growth and EPS. Thus, most will engage in this type of analysis to set up a threshold hurdle test. If the transaction doesn’t pass this muster, the acquirer may restructure the deal (cash vs. stock), change the purchase price, change the form of consideration, or pass on the deal. In this way, the exercise becomes a hurdle test that most deals have to pass - be that internally generated or externally sourced from investment bankers. The flaws of this analysis are:

It’s short-term nature (only looking at one year return vs. long-term value)

It is very sensitive to borrowing costs (interest rate) - the interest payments basically drive the value of the deal

In short, we have reviewed the last component / tool in the capital structure: equity - and the reasons why we should care about equity holders with their perceptions about a particular transaction. We briefly compare public vs. private company financial statements and went through an accretion / dilution analysis of a public company’s acquisition. We also discussed how the cash vs. stock acquisition deal structure can impact EPS percentage accretion / dilution and what management can do to tweak this percentage if it doesn’t pass the acquirer’s target accretion percentage. Lastly, we discussed the flaws of the accretion / dilution exercise. In the next post, we will discuss the buy-side acquisition process end-to-end.