M&A Blog #05 – capital structure (Part II – acquisition impact on capital structure)

In the last blog post, we discussed the impact of capital structure to an acquirer’s ability to do an M&A transaction. In this post, we will discuss the reverse: how an M&A transaction impacts an acquirer’s capital structure. Specifically, we will discuss liquidity, the amount of debt that can be raised, the amount of debt that should be raised, using the company’s debt policy as a guide, and the implication of an equity raise for financing an M&A transaction. We will use a simple Excel model to showcase the concepts.

When a company makes a large acquisition, it goes out to the capital markets and borrows – which will impact the D/E ratio at least for a while and impact the company’s flexibility. After a large acquisition, the company may not be able to do another for a period of time as it’s less cash, less liquidity position (caused by having to pay debt payments) means less flexible capital structure for a while. This flexibility issue is one that companies constantly have to revisit as it seeks growth in the marketplace. Companies with very dynamic, changing issues, price changes, and gains/losses will need a lot of flexibility – which impacts their capabilities and decisions, including around M&A.

The key determinant in accessing capital, be that debt or equity, is the value of the firm. We will discuss valuation methodologies, pros, and cons thoroughly several blog posts from now. For the moment, know that valuation is important, not only for sizing a target, but also for determining how much an acquirer can borrow. Lenders (bank and bondholders) and shareholders provide acquirers with funds to do acquisitions based on the perceived value of the acquiring companies. The amount of money that the company can borrow should serve as a cap to an acquisition. As in buying a home, a buyer may not want to use up all of the available debt it can access.

Prior to looking at any targets, an acquirer should determine:

How large a transaction it can perform with various kinds of capital

What the post-acquisition capital structure may look like

What issues should be considered in evaluating the transaction

Management should have a view of its sustainable capital structure and available debt capacity, along with incremental debt capacity provided by each acquisition (remember, each target will contribute income to the acquirer). A company’s debt capacity can be determined through analysis of cash flows to support repayments, through a discussion with lenders, and through a debt review. The lenders involve may range from senior debt provider to mezzanine or sub-debt financiers. Management can also consider using equity in financing the transaction, although as we have discussed in previous blogs, equity is more expensive than debt.

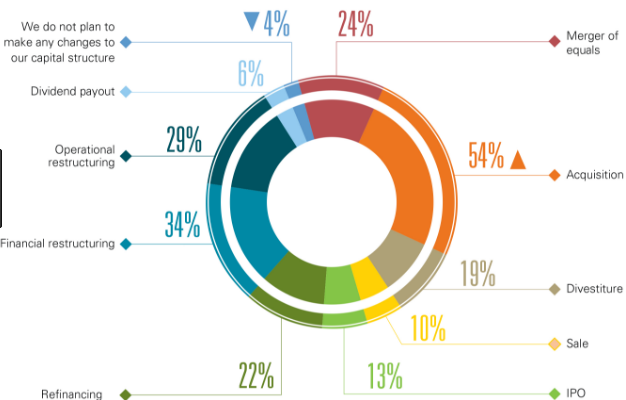

In the graphic below, we can see the impact of an acquisition to the capital structure:

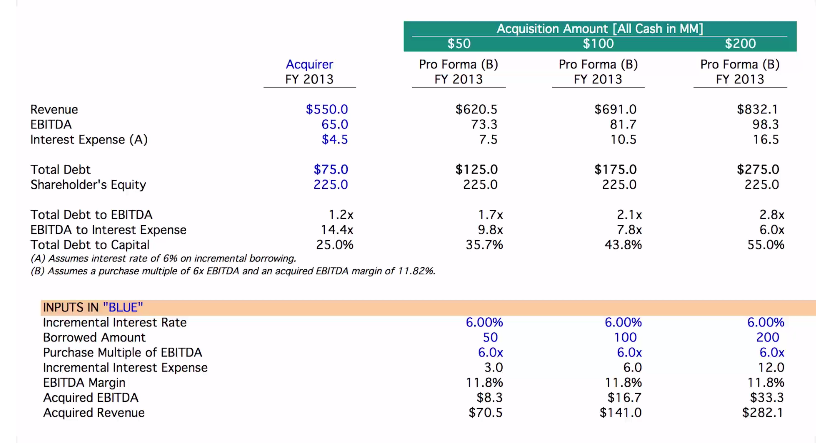

Usually, companies have a target total debt to EBITDA ratio of 4.5x to 5x max before they feel financial constraints on their ability to operate and withstand external financial shocks. Alongside the amount of money the company can borrow, this ratio should serve as one of the constraints on transaction size. To generate this total debt to EBITDA ratio, we need a few inputs:

Pre-transaction revenue, EBITDA, interest expense, total debt, and equity

Proposed transaction’s incremental interest rate (the interest rate we would likely be charged by the bank for this transaction), differing amounts that we may want to borrow, and the purchase multiple of EBITDA for the transaction (given a target and our knowledge of the market multiple for such target, what EBITDA multiple are we willing to pay for this acquisition)

In our example above, total debt to EBITDA ratio is 1.2x – a modest level that reflects the average of US public companies. Total debt-to-capital is 25%, so this company has a lot of runway to do acquisition – a lot of dry powder to do a deal.

We then looked at three possible acquisition sizes: $50MM, $100MM, and $200MM purchase prices – on cash-free, debt-free basis. We assume that equity level will remain unchanged and that we are acquiring a company that has similar EBITDA margin as our company. The assumptions can be relaxed as needed. We proceeded with the analysis as follow:

Using the Incremental Interest Rate and Borrowed Amount (purchase prices), we calculate the Incremental Interest Expense

Using the Borrowed Amount and Purchase Multiple of EBITDA, we calculate the Acquired EBITDA (this is the incremental EBITDA that the target will contribute to the parent company once it is acquired)

Using the Acquired EBITDA and assumed EBITDA margin, we calculate the Acquired Revenue of the target

The Acquired Revenue is then added to the pre-transaction revenue to yield the Pro Forma Revenue

Similarly, the Acquired EBITDA is added to the pre-transaction EBITDA to yield the Pro Forma EBITDA

Similarly, the Incremental Interest Expense is added to the pre-transaction interest expense to yield the Pro Forma Interest Expense.

Similarly, the Borrowed Amount is added to the pre-transaction Total Debt

Shareholder’s Equity remains unchanged as we assume a transaction that will only be financed through debt.

We can then calculate the Pro Forma total debt to EBITDA ratio and total debt to capital ratio.

The result of this analysis should give us a feel of how far we can push the (debt) envelope. If the acquirer has a policy of not-more-than-3x-debt-to-EBITDA ratio, then a $200MM deal is going to be a cap to the acquisition.

As mentioned earlier, we can change any of the assumptions around EBITDA margins and multiple. The main point is, this model can provide a company with a pretty good handle to the implications of further debt and at what point the company should get “uncomfortable” with a prospect acquisition.

It is common for companies to look for deals less than 50% of the acquirer’s current revenue. Any larger than that usually cause concerns around the challenges involved. A model like the one above should be used as a gauge to find the debt threshold. It would make it easier to communicate to the Board of Directors about how far a transaction can be pushed with debt alone. And it serves as a first signal to the need of further equity financing. If equity is needed, how much is needed? When should the need be communicated to shareholders? If we are dealing with a public company, when should the analyst community be notified of the dilutive equity raise? While the model can’t answer all of these questions, it can at least serve as a sounding bell before the company plunge into an acquisition it can ill afford.

In conclusion, an acquisition causes a change to the capital structure – making the company immediately less liquid post-transaction. There is a “recovery” period post-acquisition where acquirers pay down the newly-acquisition-created-debt. The amounts of debt that can be raised and that should be raised are different – the latter is typically less than the former. The amount of debt that should be raised should be carefully calculated, taking into account pre- and post- transaction financial standings. The acquirer’s debt policy should serve as a guidance to how much the debt envelope can be pushed for an acquisition. Acquirers should be comfortable in the size of their acquisition. It will make getting the Board’s approval easier and communication to the analyst community smoother. Equity should only be used in rare occasions as a dilutive equity raise sends a negative signal to the public market that the acquisition is too big for the acquirer. In the next couple of posts, we will delve deeper into debt financing and the role it can play in helping close M&A deals. The Excel file for the model above can be accessed here.