M&A Blog #14 – valuation (roles, types, equity & enterprise values)

Parties seeking to buy / sell a house typically hire an appraiser to value the property. It is no different in M&A. The core element of M&A is company valuation. Strategy, due diligence, financing, purchase price, and buyer-seller alignment all revolve around valuation and the enterprise value for the buyer and the seller. In the next few posts, we will discuss valuation theory, key methods’ strengths and weaknesses, the uses of valuation, and ways value can vary depending on the valuation purpose.

It is not an exaggeration to say that firm value is the most important characteristics in M&A. It drives prices, ROI, and financing. The challenge is: the firm’s value is not obvious or available - there is not one “true” or “correct” firm value, as any valuation is based on unknowns (future performance and future cash flow). Since valuation is highly speculative, a combination of historical analysis, comparable analysis, and projections to estimate current value are used to increase the level of accuracy (which itself depends on what happen post-transaction). Although the analysis will always be wrong when viewed from dollar and cents perspective, it is useful in narrowing the error range and making informed decisions about the prospective transaction.

Valuation focuses on two questions:

1. What is the company worth?

To answer this question, three things are needed:

The company’s intrinsic value: Typically based on cash flow streams available to shareholders, premiums paid in the marketplace, and scarcity associated with the target.

The range of value: Typically depends on performance variables (sales, margins, and capital requirements).

Any structural elements that affect the equity value: Typically includes differences between public vs. private valuations, minority vs. control premiums, insider ownership, sizeable equity offerings, etc.

2. What will someone pay for the company?

To answer this question, four things are needed:

The list of potential buyers: Strategic buyers tend to be willing to pay more than financial buyers (but typically with longer duration of due diligence). There are also structural differences of past acquisitions to take into account.

The list of the sector’s active buyers: The acquirer’s own current market valuation can come into play. Do they have the cash of debt/equity capacity to bid aggressively? The status of the acquirer’s own share price will impact its acquisition currency.

The market conditions

The context of the transaction: Privately negotiated sale will have different mechanics than an auction. Whether the sale is hostile or friendly also matter significantly.

It is worth noting that new businesses (startups and early stage companies) require a different method of valuation than mature and later-stage companies. This requirement is due to the fact that an early stage company doesn’t have much financial historical data to fall back on and that the majority of the company’s value comes from its growth potential in the future. Some experts argue that valuation on startups and early stage companies is much harder than on mature and later-stage companies.

A company’s value depends on the type of transaction being considered, the buyer’s identity, the way the purchase price is negotiated and ultimately determined, and the level of liquidity created by the transaction. Some examples of different types of valuation are:

Internal Transaction vs Arm’s-Length Purchases:

Internal transactions can be partner agreements to buy each other out at some point, senior employees’ contractual rights to buy into the company, rights allowing family members to acquire shares, and more. These equity transactions between related parties are not negotiated purely on economic / financial terms. Their valuations tend to be materially lower than an arm’s-length deal.

Buy-Sell Agreements:

These agreements typically stipulates that a private company’s shareholders seeking liquidity must first offer shares to other shareholders at a predetermined price. In other words, the company or its other shareholders can buy back a shareholder’s outstanding shares at a predetermined valuation (typically less than a 3rd-party acquisition).

Estate Planning:

Private companies’ shares can be transferred to family members as a part of a shareholder’s estate. To minimize taxes on these transfers, low valuation on the transferred shares is common.

Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP):

ESOPs are programs that allow employees to become partial owners of firms, typically through equity shares as a part of compensation. When an employee retires, the company must provide a full / partial buyout of accumulates shares in a defined time period. An aggressive premium tends to be unaffordable to the company, so an ESOP valuation is typically done at a discount to market valuation.

Control vs. Minority:

A controlling share has significantly more value than a minority share, especially for a private company. While public company controlling premium can be around 20%, a private company controlling premium can go as high as 50%. Private company shareholders often have fewer protections from a takeover than public shareholders.

Public and Private Market Valuations:

Public company valuations are higher than private company with the same performance metrics because of the liquidity feature provided by the stock market that doesn’t include a sales process of a significant part of the company. This liquidity feature typically creates a private company discount of around 25-35% range. In addition, while public companies have an observable valuation mechanism through their publically trading prices, private companies require a market test (approaching potential interested buyers for their interest) or through the application of valuation methods (such as precedent transaction and others that we will discuss in the next posts) to determine a proper value.

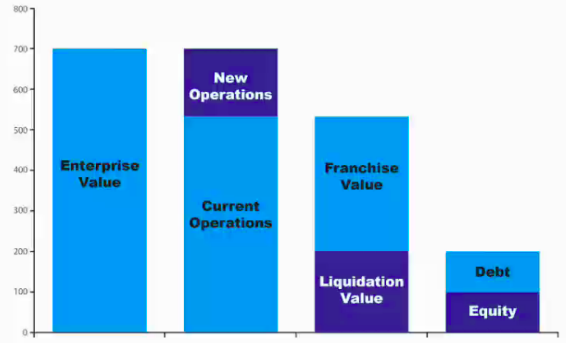

The last concept we will discuss in this valuation post is equity and enterprise value. The differences between the two are:

Equity Value:

This is the residual value to common shareholders after all debts and secured liabilities are repaid, also known as market value, offer value, shareholders’ interests, and market capitalization. It is calculated as the share price times the fully-diluted shares outstanding.

The fully-diluted shares outstanding is the sum of basic shares and diluted shares, the latter is calculated by converting all unconverted shares from stock options, convertible bonds, preferred shares, and warrants into stock. We will discuss these equity-like instruments in our next post when we discuss data preparation for valuation.

Enterprise Value:

This is the full valuation of the firm that includes all form of capital - such as equity, debt, cash, preferred stock, and minority interest - which is also known as firm value, enterprise value, transaction value, aggregate value, and adjusted market value. It is calculated as the Equity Value plus Net Debt plus Preferred Stock plus Minority Interest.

The process for arriving at the overall valuation and its components will be different for a public and a private companies. For a public company, the equity value is readily available, so calculating the enterprise value is typically more straightforward. For a private company, the opposite is often true. The enterprise value is established using valuation techniques or buyer valuations. The equity value is then determined by subtracting net debt, preferred stock, and minority interest from the enterprise value.

So, to re-cap, we have discussed the roles and types of valuations commonly practiced in the market. We have also discussed the differences between equity value and enterprise value. These concepts will be very important in the next few posts as we discussed the specifics of different valuation methods such as Discounted Cash Flows, Comparable Company, Precedent Transaction, Dividend Discount Model, and more. It is important to remember that there is no one “true” of “correct” value to a company. So many elements factor into company valuations (the buyer’s identity, the context of the transaction, the market condition, and more) that the best one can do in valuation is to narrow the range of error of the exercise so informed decisions can be made in guiding the transaction forward.