M&A Blog #19 – valuation (Leveraged Buy Out - LBO)

Thus far, we have discussed three common valuation methods that most strategic and financial acquirers use when valuing a company for acquisitions or investments. This current post about Leveraged Buy Out (LBO) is about a valuation method used by a very specific type of financial acquirer: private equity (PE) firms. While this method is not usually used by strategic acquirers (corporations) to justify their offers, savvy strategic acquirers do perform the analysis to figure out what a PE competitor in an auction environment would be willing to pay for a target. Indeed, that is the scenario that I’m familiar with. The steps in this post should be viewed from that regard as I’m sure that real PE firms (which I’ve not had the pleasure to be a part of) perform more complex LBO calculations than the one laid out here. Nevertheless, like the other valuation methods we have covered to-date, the broad strokes (steps) are the same.

As I mentioned in my valuation preparation post, LBO is a valuation method that uses the assets of the acquired and the acquiring companies as well as cost of borrowing money for acquisition to find the value estimate of a potential investment as measured by its internal rate of return (IRR). In this post, we will discuss the mechanics of LBO step by step, starting from the point where all the needed tools and data for such analysis as outlined here have been gathered. Lastly, I would be remiss if I don’t mention that some companies do perform LBOs when management considers taking the company private (from a public status), usually with the help of a PE firm.

The major steps of LBO are:

Building the Sources and Uses tables.

Building a proforma balance sheet.

Deriving assumptions for the future income statement and balance sheet.

Building a historical 3-statement model and a debt-interest schedule.

Building the go-forward 3-statement model.

Building the go-forward debt-interest schedule.

Modeling the future exit.

Compiling a summary of relevant financial statistics to illustrate key financial metrics during the holding period.

Performing sensitivity / scenario analysis using Monte Carlo analysis.

We will delve deeper into each steps above in the following paragraphs of this post. It is worth noting that each step can justifiably warrant an entire post in itself. For the purposes of this post though, we will keep matters concise by discussing only the most practical and commonly accepted aspects of each step.

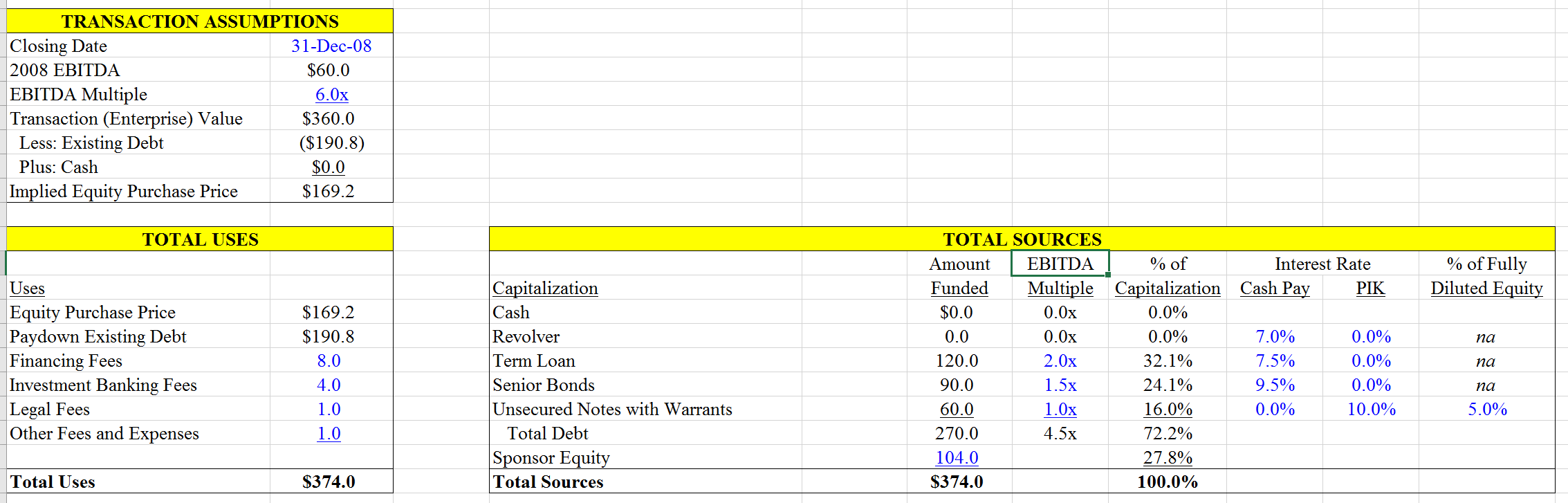

The 1st step in LBO is to build a Sources and Uses table. For this exercise, we need the most current EBITDA, debt balance, and cash balance from the target’s historical income statement and balance sheet; as well as the EBITDA multiple that we will use for the proposed transaction. We then calculate Implied Equity Purchase Price as follow:

Transaction (Enterprise) Value = Most current EBITDA * EBITDA Multiple.

Implied Equity Purchase Price = Transaction Value - Debt + Cash.

Once we have the Implied Equity Purchase Price, we can build the Uses table by factoring in the pay down of existing debt and various transaction fees (financing, investment banking, legal, and other fees) related to the proposed transaction as follow:

Total Uses = Implied Equity Purchase Price + Paydown of Debt + Fees.

Knowing the amount of money that is needed for the proposed transaction (Total Uses), we proceeded with the building of the Sources table. For this table, recall that LBO transactions are heavily financed with debt (it can go up to 90% of the capital structure for some deals). Therefore, it is absolutely crucial that we know what debt instruments will be used in the proposed transactions. Instruments such as revolving loans (revolver), term loan, senior bonds, unsecured notes (usually with equity-like sweetener such as warrants), and more. If these instruments can’t fully cover the Total Uses $ amount, the difference is the amount that the financial sponsor (the PE firm) will have to finance out-of-pocket from their fund. Each instrument’s portion of the transaction is typically expressed as a multiple of the EBITDA and the sum of cash (from the target’s balance sheet, used to finance the proposed transaction), debt instruments’ $ amount, and sponsor’s equity has to sum up to 100% (otherwise, there will portion unpaid and the transaction is a no-go).

The next (2nd) step of LBO is building a proforma balance sheet. For this step, we would need the target’s most current balance sheet, the Implied Equity Purchase Price, the book value of equity (from the target’s most current balance sheet), the amortizable transaction fees (such as financing fees), the non-amortizable, must-be-expensed transaction fees (such as investment banking, legal, and other fees), and the new debt information. We proceeded as follow:

New Goodwill = Implied Equity Purchase Price - Book Value of Equity.

New Intangible Assets = the sum of Amortizable Transaction Fees.

Transaction Fees to be Expensed at Closing = the sum of non-amortizable transaction fees.

We then lay out the historical balance sheet side-by-side with the financing and transaction adjustments. The latter consists of the following calculations:

Amortizable Intangibles = New Intangible Assets.

Goodwill = New Goodwill.

Target’s Existing Debts = the opposite (or negative) amount of the current amounts. This is because these debts will be paid off at closing of the proposed transaction.

New Debt Instruments = types and amounts from the Sources and Uses table we calculated in the previous step.

Retained Earnings = the opposite (or negative) amount of the current amount - the Transaction Fees to be Expensed at Closing.

Common Stock = the opposite (or negative) amount of the current amount + the Sponsor’s Equity from the Sources and Uses table.

The final part of this step consists of laying out the proforma balance sheet with entries that are the sum of the historical balance sheet’s entries and the adjustments entries. Any total entries should be calculated as the sum of corresponding entries in this proforma balance sheet.

The 3rd step of LBO calls for deriving assumptions for the future income statement and balance sheet. To proceed with this step, we need the historical income statement and balance sheet. We then proceeded with calculating historical figures as follow:

Income Statement Assumptions:

Revenue Growth Rate = this year’s Revenue / last year’s Revenue -1.

COGS as % of Revenue = COGS / Revenue.

Depreciation as % of Gross PPE = Depreciation / Gross PPE.

Amortization = reflected in the historical balance sheet.

Amortization Period (in years) = the PE firm’s holding period (usually 5 to 7 years).

SGA as % of Revenue = SGA / Revenue.

Other Income / Expenses = Other Income / Expenses.

Tax Rate = Taxes / Pretax Income.

Balance Sheet Assumptions:

Days Accounts Receivable (AR) = AR / Revenue * 360.

Days Inventory = Inventory / COGS * 360.

Other Current Assets = as reflected in the historical balance sheet.

Other Assets = as reflected in the historical balance sheet (Amortizable Intangibles).

Capex as % of Sales = - Capital Expenditures / Revenue.

Asset Disposition = as reflected in the historical Cash Flow Statement’s cash flow from Investing’s Asset Disposition.

Days Payable = Accounts Payable / COGS * 360.

Accrued Liabilities as % of COGS = Accrued Liabilities / COGS.

Other Current Liabilities as % of COGS = Other Current Liabilities / COGS.

Other Liabilities = as reflected in the historical balance sheet

Debt Instruments’ Interest Rate Assumptions:

LIBOR = the prevalent LIBOR rate at the time of the analysis.

Interest earned on cash = the prevalent cash interest rate at the time of the analysis.

Revolver, Term Loan = as % to LIBOR.

Senior Bonds’ and Unsecured Debt’s Cash and PIK Interests = fixed interest rate during the holding period (since it is determined at the transaction closing time).

Amortization = New Debt’s Term Loan spread over the holding period.

The 4th step in LBO is to build the historical 3-statement model and debt-interest schedule. The 3-statement model is basically the historical income statement, the balance sheet, and the cash flow statement stacked one on top of the other. The historical cash flow statement can also be derived from the income statement and the balance sheet. For the purpose of this exercise, we would also need the following four elements:

Beginning Cash Position = from the balance sheet.

Change in Cash Position = from the cash flow statement (total cash flow).

Ending Cash Position = Beginning Cash Position + Change in Cash Position.

Cash Flow before Revolver = Cash Flow from Operation + Cash Flow from Investing + Change in Term Loan + Change in Senior Bonds + Change in Unsecured Debt + Beginning Cash Position.

The historical debt-interest schedule is basically each old (existing) debt instrument’s beginning balance, pay down / draw down schedule, ending balance, and interest data (rate and dollar amount, for both the cash interest and the PIK interest). The total interest expense and cash interest expense are then calculated by summing up the corresponding elements from each debt instruments. The Interest Earned on Cash is then calculated by taking the average of the last two years of cash on the balance sheet, multiplied by the Interest Earned on Cash Assumption from the previous step.

The next (5th) step in LBO is to build the go-forward 3-statement model. The go-forward income statement is build by applying the Income Statement Assumptions from the 3rd step to the historical income statement from the 4th step, with references to the appropriate go-forward balance sheet and debt-interest schedule entries. Because the go-forward balance sheet and debt-interest schedule entries will be calculated later, the initial go-forward income statement will have incorrect entries until the other two go-forward statements are fully built. The go-forward balance sheet is built using a similar approach to the go-forward income statement, with one exception: the proforma balance sheet from the 2nd step is inserted in between the historical balance sheet and the go-forward balance sheet, replacing the historical balance sheet for the go-forward calculations. We then proceed as follow:

Assets

Cash = from the go-forward Cash Flow Statement’s ending cash position.

AR = Days Account Receivable assumption (from earlier) / 360 * this year’s Revenue.

Inventory = Days Inventory assumption (from earlier) / 360 * this year’s COGS.

Other Current Assets = from assumption earlier.

Total Current Assets = Cash + AR + Inventory + Other Current Assets.

Gross PPE = prior year Gross PPE - go-forward Capex and Asset Disposition (from go-forward cash flow statement).

Cumulative Depreciation = prior year Cumulative Depreciation + this year’s Depreciation from the go-forward Income Statement.

Net PPE = Gross PPE - Cumulative Depreciation.

Amortizable Intangibles = prior year Amortizable Intangibles - this year’s Amortization from the go-forward Income Statement.

Goodwill = from prior year (proforma) Goodwill. This value will be the same through the rest of the holding period.

Total Assets = Net PPE + Amortizable Intangibles + Goodwill + Total Current Assets.

Liabilities

Accounts Payable (AP) = Days Payable assumption (from earlier) / 360 * COGS.

Accrued Liabilities = Accrued Liabilities as % of COGS assumption (from earlier) * COGS.

Other Current Liabilities = Other Current Liabilities as % of COGS assumption (from earlier) * COGS.

Total Current Liabilities = AP + Accrued Liabilities + Other Current Liabilities.

Existing Debt Instruments = from the prior year (proforma) balance sheet.

New Debt Instruments = from the debt-interest schedule’s ending balances of the corresponding instruments.

Other Liabilities = from assumptions earlier.

Total Liabilities = Total Current Liabilities + Existing Debt Instruments balances + New Debt Instruments balances + Other Liabilities.

Shareholder’s Equity:

Retained Earnings = prior year (proforma) Retained Earnings + Net Income.

Common Stock = prior year (proform) Common Stock. This value will be the same through the rest of the holding period.

Total Shareholders Equity = Retained Earnings + Common Stock.

Total Liabilities and Equity = Total Liabilities + Total Shareholders Equity.

Check = Total Assets - Total Liabilities and Equity. Should be zero (this is an error check for the balance sheet must balance rule).

The go-forward cash flow statement can be derived from the go-forward income statement and balance sheet. For the purpose of this post, I assume folks who understand how we get to this point already have an understanding of how a cash flow statement can be derived from an income statement and a balance sheet. A link to the sample file which we have used thus far in this post (and contains the details on how the go-forward cash flow statement can be derived from the income statement and balance sheet) will be provided towards the end of this post. I may also post the mechanics of that step in a future post. For now, we will proceed with building the go-forward debt-interest schedule.

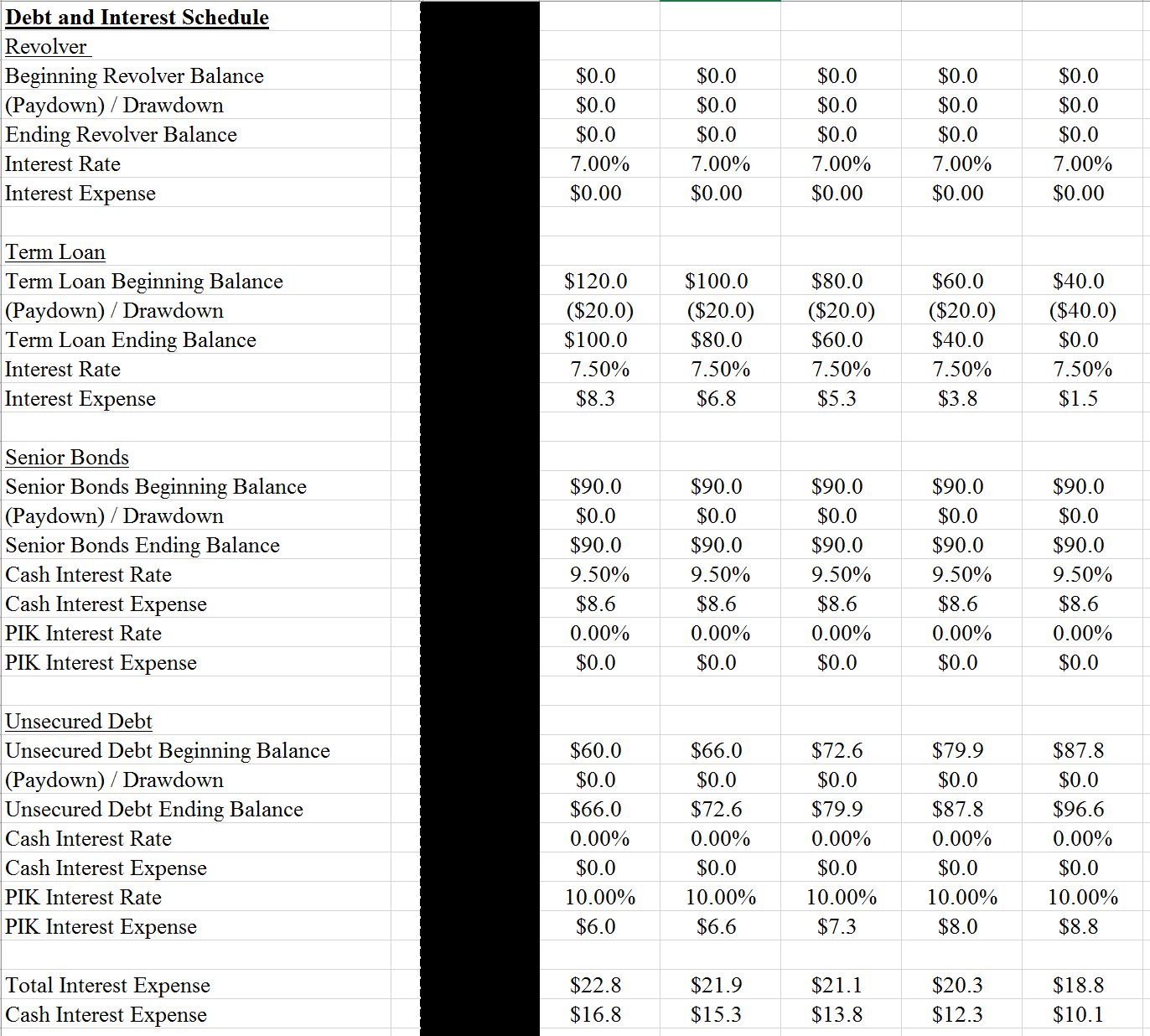

The 6th step in LBO is to build the go-forward debt-interest schedule. Like the historical debt-interest schedule we encountered earlier, the go-forward version is basically each new debt instrument’s beginning balance, pay down / draw down schedule, ending balance, and interest data (rate and dollar amount, for both the cash interest and the PIK interest). We proceed with each instrument’s calculations as follow:

Beginning balances:

For the first go-forward year in the holding period, it is basically the balances from the prior year (proforma) balance sheet.

For the following go-forward years afterward, the beginning balances are the respective instrument’s ending balances of the previous years.

Pay down / Drawdown:

Revolver = -MINIMUM (Cash Flow Before Revolver from earlier, Beginning Revolver Balance). The ‘-’ (negative) sign before the MINIMUM signals paydown, and the rest of the formula basically states that the paydown amount will only be as much as free cash flow to pay the revolver balance and never more than what is owed.

Term Loan = from assumptions earlier (Term Loan Amortization).

Senior Bonds, Unsecured Debt = from assumptions earlier, these instruments are not typically amortized, rather they have a bullet payment with interest at the end of the load (holding) period.

Ending Balances = Beginning Balances - Pay down / Drawdown.

Interest Rate: from assumptions earlier.

Interest Expense:

Revolver, Term Loan, Senior Bonds Cash, Unsecured Debt Cash = Interest Rate * the average of beginning and ending balances.

Senior Bond PIK, Unsecured Debt PIK = Interest Rate * the beginning balance.

Total Interest Expense = the sum of all Interest Expense (Cash and PIK).

Cash Interest Expense = the sum of all Cash Interest Expense.

Interest Earned on Cash = the average of the last two years of cash on the balance sheet * Interest Earned on Cash assumption.

It is worth noting at this junction that the debt-interest schedule, specifically the revolver portion of it, functions as a plug to the 3-statement model; very similar to the plugs we used in DCF a while back. Also, because the 3-statement model and the debt-interest schedule built on one another, there is a circular reference in the model that requires disabling automatic calculation in Excel. The step to do so is: go to File >> Options >> Formulas >> under Workbook Calculation, select Manual >> under Enable iterative calculation, select 1000 for Maximum Iterations.

The next (7th) step in LBO calls for modeling the future exit. This step is relatively straightforward:

Transaction Value = the last year’s EBITDA in the go-forward Income Statement * the EBITDA multiple we use to enter the transaction earlier.

Total Debt = the sum of the new debt in the last year of the go-forward balance sheet.

Cash Balance = from the last year’s Cash on the go-forward balance sheet.

Transaction Fees = assume 1% of the Transaction Value + $2 million for legal and other fees.

Equity Value = Transaction Value - Total Debt + Cash - Transaction Fees.

% Equity to Sponsor = the part of the company that the PE firm owns = 1 - the part that is own by lenders (usually the unsecured debt lender who holds warrants).

Equity to Sponsor = Equity Value * % Equity to Sponsor.

% Equity to Unsecured Lender = the part of the company that the unsecured lender owns.

Equity to Unsecured Lender = Equity Value * % Equity to Unsecured Lender.

IRR to Sponsor:

Initial Equity Investment = lay out the sponsor’s equity investment year-by-year during the holding period.

Dividends = lay out the target’s planned dividends year-by-year during the holding period.

Proceeds at Sale = Equity to Sponsor calculated earlier.

Total Cash Flows to Sponsor = Initial Equity Investment + Dividends + Proceeds at Sale.

IRR to Sponsor = IRR(Total Cash Flows to Sponsor).

IRR to Unsecured Lender:

Initial Loan = lay out the lender’s loan year-by-year during the holding period.

Cash Interest Received = lay out the lender’s planned cash interest received year-by-year during the holding period.

Principal Repayment at Sale = Unsecured Debt Ending Balance from the last year’s go-forward debt-interest schedule.

Equity from Warrants at Sale = Equity to Unsecured Lender calculated earlier.

Total Cash Flows to Lender = Initial Loan + Cash Interest Received + Principal Repayment at Sale + Equity from Warrants at Sale.

IRR to Lender = IRR(Total Cash Flows to Lender).

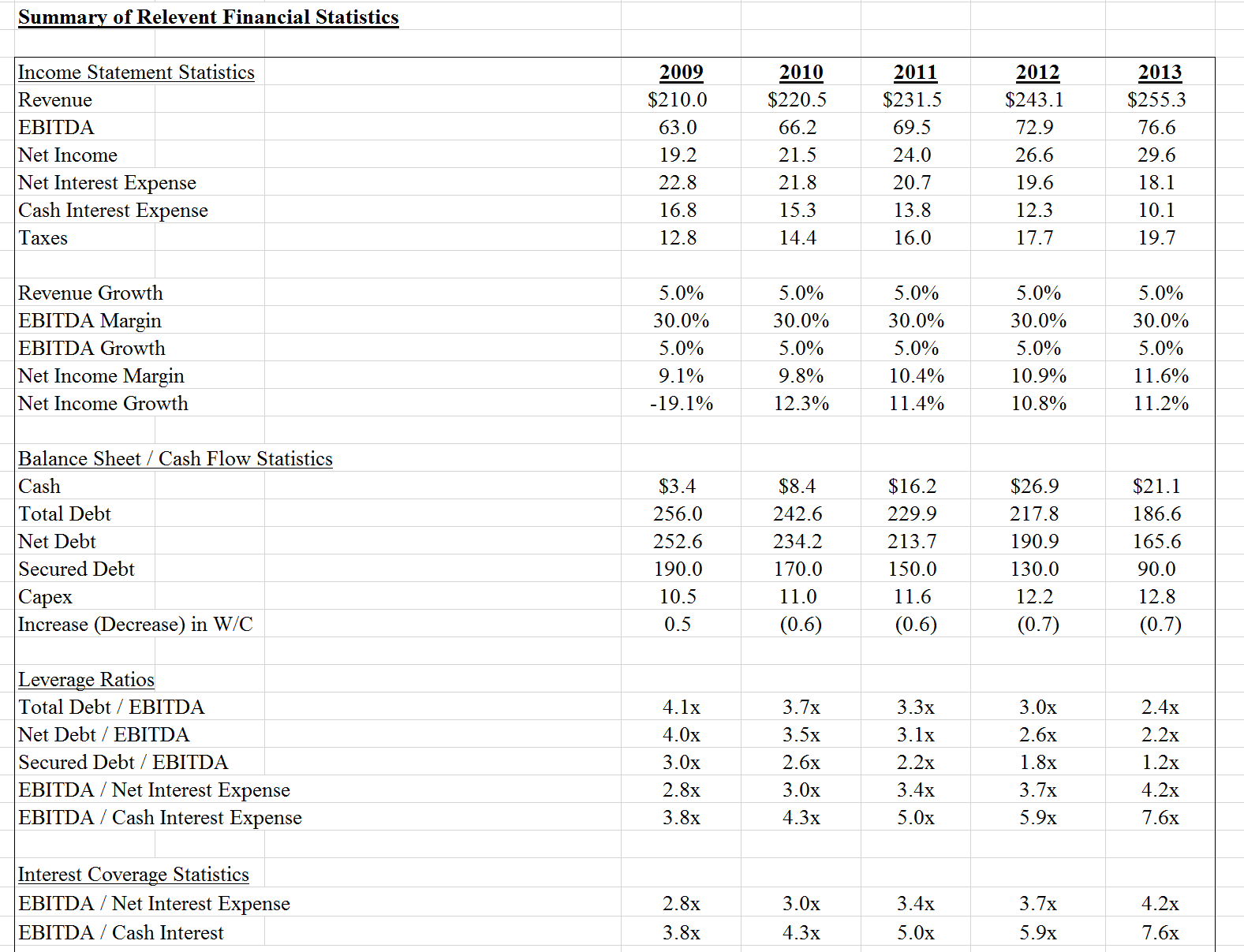

The 8th step in LBO calls for compiling a summary of relevant financial statistics to illustrate key financial metrics during the holding period. These include Income Statement Statistics, Balance Sheet and Cash Flow Statistics, Leverage Ratios, and Interest Coverage Ratios. The calculations of these statistics are beyond the scope of this post, but I want to highlight it here as it is a common step in LBO. A link to the sample file which we have used thus far in this post (and contains the details on how these statistics can be calculated) will be provided towards the end of this post. I may also post the mechanics of this step in a future post.

The 9th and final step in a proper LBO method is to perform sensitivity / scenario analysis, preferably using a Monte Carlo simulation. Because this step is similar in this method as it is in the other valuation methods (DCF, Comparable Company, etc.), we will discuss sensitivity / scenario analysis in great details in the last post of this valuation series in 2-3 posts from now. The sample file for our LBO analysis can be accessed here.

As we can tell from the steps laid out thus far, LBO has advantages and disadvantages. The advantages include its ability to provide investors and acquirers with a detailed snapshot of the target’s historical growth and financial strengths. The exercise also help determine a fair price on a standalone basis (without synergies) and how much debt the acquirer can take on to close the transaction. LBO’s disadvantages include its far from exact science, its heavy reliance on past data (which doesn’t take into account future uncertainties) and assumptions.

So, to recap, we have discussed the development of an LBO model and its supporting elements, along with its strengths and weaknesses. Given its advantages and disadvantages, LBO is best used in conjunction with other valuation methods (like DCF and Comparable Company). It is only then that the closest-to-correct value of the target can be deduced via comparison. In the next post, we will discuss another valuation method, Dividend Discount Model (DDM).