M&A Blog #12 – sell-side acquisition (preparation)

Buying and selling a company has many overlaps to buying and selling a house. There are many reasons to sell a house: wanting liquidity and diversification (especially if the house is an investment property), lack of progress toward a financial / strategic goals (i.e. the house failed to increase in expected value), mature market (i.e. the house sits in a geography that is not expected to increase in value anymore), lack of financial resources to pay for the house, estate-planning (i.e. inheritance), and conflict among owners (i.e. divorce, etc.). Many of these causes have their equivalences to the reasons behind the sale of a company (also known as a divestiture):

Liquidity: As the equity holding period matured, investors (private equity funds behind companies) will look to sell. PE funds typically have 4-to-7-years ownership windows for an investment and look for an exit at the end of that period through a sale or an IPO (initial public offering).

Diversification: When private business owners or investors found themselves too heavily invested in one business / industry segment (niche), they may look to diversify their assets to counter investment risks.

Lack of financial / strategic progress: Shareholders’ frustration with the lack of growth of a company’s stock price / dividends / earnings per share / other financial metrics may drive exits.

Peaked market valuations: When market cycle peaks or an industry fully matures, it may be advantageous for shareholders to cash out.

Business adversity: An economic downturn, the loss of a major customer or the company’s key individual leader, an adverse market / political condition may drive shareholders to other investment alternatives.

Lack of financial resources to grow: Lack of capital to properly market, R&D, and/or acquire may drive shareholders elsewhere.

Consolidation: As industry sectors such as beverages, retail, industrial distribution, and more matures; consolidation forces companies and shareholders to re-think competitive and investment positions.

Estate-planning, health, or tax reasons: Aging shareholders may shift investments as influenced by investment goals and tax policies.

Shareholders conflict: Differing risk tolerances, liquidity needs, and strategic views may drive shareholders and investors to put a company up for sale.

Regardless of the base reason(s), the current owners and management of a company looking for a new owner should seek to:

Maximize return on investment for current owners.

Minimize the effect on the company’s other stakeholders (employees, customers, vendors, and local community) as long as doing so doesn’t forfeit the highest possible return.

The decision on who becomes the ultimate acquirer may also depend on expectations such as whether the new owner will maintain jobs, presence in the current community, and more.

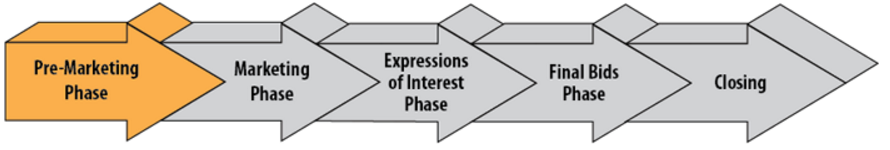

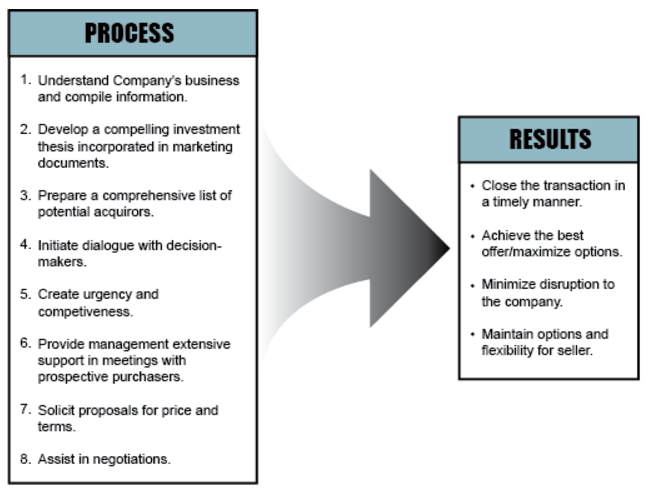

Once a sale has been decided, the process to look for a new owner is pretty well established. Most companies, especially those with $20 million or more in sales, will engage an investment banker or professional advisor to manage the sale process (smaller companies will typically engage a broker-dealer). The process starts with preparing the company for sales by developing marketing and informational material to distribute to prospective buyers. The overall divestiture process looks like:

To support the seller’s management team in achieving an acceptable goal, this process is designed to streamline the path to a transaction closing. Time is not a seller’s friend. An open-ended process distracts management, can cause corporate performance to suffer, and opens the possibilities for adverse market conditions. All of which can result in underperformance and negative adjustments to the purchase price, raise buyer concerns about material business changes, and undermine the credibility of information already provided (which may lead to prospective buyers to look closer at their assumptions). Simply put, not following a defined process can impact the seller disproportionately.

On the other hand, there are many advantages of following a defined process including: having a level of confidentiality throughout the process, minimizing the seller’s resources vested into the process, providing sufficient information for prospective buyers to make an informed decision, and putting competitive pressure on prospective buyers to make favorable offer. The divestiture process vary in lengths, a typical timeline lasts between 6 to 12 months. Factors such as degree of preparation required of the seller, due diligence depth required by the buyer, and the demand from the buyer universe affect the length of this process.

When dealing with prospective buyers, preparation is key. The company’s financial and strategic position should be communicated accurately and favorably. The exercise of developing information that paints the company in the best light while maintaining a high degree of accuracy can be delicate. Any discrepancy between the provided information and actual condition found through due diligence will undermine the credibility of the sales process. So pre-sale planning should be undertaken seriously.

Seller should be prepared that every activity in the last three years will be scrutinized, so a seller should minimize financial and operational surprises that can be found in due diligence. At the minimum, seller’s management and shareholders should ask the following questions:

* Courtesy of Professor Tom Harvey, Penn State University, 2017

As we see in the above diagram, P&L or income statement gets a lot of focus in the divestiture process - even more so when the target company is privately owned. In an earlier M&A post, we have discussed how private companies’ accounting statements differ from public companies’. As private companies seek to minimize taxes and public companies seek to maximize earnings, there are a number of adjustments that need to be made before apple-to-apple comparisons can be made. These adjustments usually fall into:

Compensation and perks adjustments: private companies’ management and shareholders tend to pay themselves above market compensation. They may run perks such as personal expenses (travel, car, country club memberships, etc.) through the business to minimize earnings and taxes. Such expenses overstate the business’ cost structure and need to be added back to earnings.

Non-recurring one-time charges: unusual expenses that negatively affect the historical cash flows misleadingly should be added back to earnings. These expenses include a large write-off of receivables due to a customer’s bankruptcy, ERP system installation, force majeures (fire, flooding, earthquakes, etc.), and more.

Elimination of costs post-transaction: any cost that the target won’t incur under a new ownership, such as: key-person insurance, credit insurance, etc.

Normalizing capex versus expenses: to minimize earnings, private companies expense investments that should be capitalized. These expenses, such as the installation of an IT system, should be normalized by capitalizing them.

Once an adjusted income statement is developed, the investment banker then develop a CIM (confidential information memorandum, also known as offering memorandum), which is one of the two deliverables from this pre-marketing phase. The memorandum contains information that allows a prospective buyer to assess the target intelligently and a carefully crafted story that identifies the company’s most important investment attributes and potentials. A prospective buyer should be able to decide on their level of interest for the acquisition and the approximate value for the target after reading the memorandum.

The document usually contains: a company overview (description, history, the reason(s) it is up for sale), investment thesis (benefits / opportunities of acquiring the target), industry overview (major competitors and customers, industry structure, etc.), product / service review (leading products and differentiators), customers (the target’s top 10 customers, sales concentration, lengths of customer relationships, level of geographic distributions, and other indicators for the stability and strengths of customer relationships), marketing and sales (the way the company go to market - either directly, using retailers, using distributors, etc.), operations (the way the company manufacture or service its products - in-house vs. assemble from suppliers), and financials (historical financial statements, typically audited; along with a 3-year forecast that clearly outlines supporting rationale for the target’s growth).

The second deliverable that a seller should expect from its investment banker in this phase is a buyers list - a list of potential buyers in detail and the rationales of when these buyers should be contacted. Different buyers have different reasons to engage in a sale process, it is helpful to know what each motivation is to extract the most value for the seller. The banker should help the seller in navigating between the following types of buyers:

* Courtesy of Professor Tom Harvey, Penn State University, 2017

Developing a buyers list require market insight and knowledge of each buyer that should answer the following questions:

Who are the target’s current direct competitors?

Who are the companies that are not direct competitors today that might benefit from owning the target?

What are the recent (less than 5 years old) acquisition activities in this industry segment? Who are the active acquirers?

As it is, the universe of buyers can be simplified to strategic buyer and financial buyer as follow:

Direct Competitors: strategic buyer, especially those with previous acquisition records.

Overlapping Product / Service Providers: strategic buyer, with 1 or more overlapping market segments.

PE Portfolio Companies: strategic-financial buyer, typically focus on adding on to current product / service offering, market geography, or customer types.

PE Firms: financial buyer, for add-on acquisitions or new platform investments (larger acquisitions that serve as a basis for additional investment). Typical targets for platform investments are companies with strong operations and management teams, as well as leverageable assets.